It's common for fans to get exhausted by the media's

over-coverage of a player and begin to take it out on that player. It becomes popular to deem the player "overrated." It's

happened with Tebow, Manziel and Bridgewater in recent years. After watching him in every single snap this season, I can say that it shouldn't happen with Jameis Winston.

Note that the images and gifs below are intended to demonstrate the qualities or tendencies I'm discussing, not to prove that Winston possesses those things. In other words, I can't post every single example of Winston being accurate and inaccurate to prove his accuracy, but I tried to share some of the most impressive examples.

Strengths

Size. Winston has prototypical size: 6'4" and 228 pounds.

Arm strength. By

now you should have seen the videos of him throwing baserunners out from rightfield,

clocking 96 mph fastballs and tossing footballs over the Pike House.

I'd rate his arm strength a 9/10 — it's not the strongest I've seen,

but there is not a single throw he can't make.

Watch the cornerback on this play: He breaks on the throw immediately but has no chance. Throwing behind the squat cornerback in Cover 2/Tampa 2 is

among the more difficult things to do as a quarterback, but Winston makes it

look easy. It doesn't matter if you’re playing on Saturday or Sunday (or

Thursday or Monday) — the corner isn't going to break up a pass that has this much velocity.

There are enough examples of Winston's arm strength in the

rest of my analysis that I won't waste any more space discussing it — except to

share this gif.

Throwing this ball is a terrible decision, but effortlessly

throwing a ball 35 yards while falling down is impressive.

Accuracy and ball

placement. When you complete 67.9% of your passes in an offense that

doesn't feature many screens and quick throws (ahem, air raid QBs), you're an accurate passer. But

to be elite, throwing a catchable pass isn't enough; you also have to be able

to recognize where the ball needs to

be based on the defender's leverage and get it there. That's ball placement.

Here's a simple example of good ball placement. Targeting

the seam route, Winston throws behind the receiver to avoid the linebacker in

the middle. Winston's awareness of ball placement is clear in nearly

every throw he makes. Here are a few more examples of his incredible accuracy.

Winston avoids the pass rush, keeps his eyes downfield and

puts this ball where only his guy can catch it in double coverage.

Here's a great demonstration of arm strength and accuracy.

This ball was thrown from the 25-yard line while Winston was rolling to his left. The receiver doesn't even break stride.

This is an NFL throw. The defense runs a fire zone

blitz (three deep and three underneath coverage). Winston sees the safety, the deep

middle 1/3 defender, vacate his zone to chase the slot and hits the outside

receiver on the post. This ball is perfectly placed. Notice also how quickly Winston makes the decision to throw when the safety turns his hips — that awareness fits into the football IQ category.

Football IQ. This

is more difficult to demonstrate, but it becomes clear watching a quarterback

before the snap and seeing how often he looks confused immediately after the

snap. I could count on one hand how many times I saw Winston look surprised by

a defense after the snap.

I went ahead and labeled this coverage, but it's not easy to

diagnose pre-snap. It could be Cover 6 (also known as Quarter-Quarter-Half, it's Cover 2 to the boundary,

Quarters to the field); Cover 0 corner blitz (man with no deep safety), with the boundary safety creeping over to cover the single-side receiver so that the boundary corner can blitz; or even Cover 3 (three deep, four under), with the

boundary corner bailing to the deep 1/3 at the snap.

Winston recognizes Man Free (man coverage with one deep

safety), watches the safety and throws away from him. The short route by the

outside receiver keeps the cornerback low, clearing space for the slot receiver

to work behind him.

Winston doesn't do much after that except deliver a perfect

ball.

I will say that there's room for Winston to improve his deep accuracy — though it's still outstanding — and he occasionally overthrows intermediate routes, which can lead to interceptions when you're throwing over the middle.

Pocket presence. Winston

is excellent against outside pressure and good against inside pressure. He has

no qualms about taking a hit to deliver a pass, is very comfortable stepping

into a pass rush and knows when to scramble.

Despite his size, he frequently eludes the rush; when he

can't, he's strong enough to fight through tackles. And the best part is that

he keeps his eyes downfield.

Mobility. Winston

is a capable runner but not a deadly one. He's not particularly fast (his 40 time is listed as low as

sub-4.6, but he looks like a 4.65 to me); he'd rather throw than run; and he

isn't going to break off a long run like Marcus Mariota (his longest run this

season is 20 yards).

Weaknesses

My list of weaknesses for Winston demonstrate just how

difficult it is to find flaws in his game.

I wouldn't consider it a huge weakness, but as far as

mechanics his delivery isn't as compact as it could be — he tends to drop the

ball when he starts his motion.

There are also a few

instances where his footwork broke down. For example, sometimes he adds an unnecessary bounce at the end of his drop. Neither

of these things should concern pro scouts.

Ball handling and

security. Winston's play fakes aren't good, but that's not a big deal. More

concerning is that he's lax with the ball when he starts scrambling.

Even when he tucks the ball to run, he tends to hold it loosely. He usually gets away with it in college because he's so strong, but

it's something he needs to clean up.

Doesn't check down or

throw the ball away. This is the real weakness in Winston's game right now. There are half a dozen examples in every game.

A toss to the running back at the top would have been an easy first down, and even throwing to the shallow crossing route would have yielded better results. Instead, Winston invariably tries to extend the play when he feels pressure.

On these bootlegs, you're supposed to throw the flat route if you feel pressure early.

I think I saw maybe three plays in the entire season where Winston threw the ball away. There's no good reason for this not to have been the fourth.

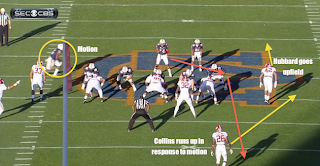

On this play vs. a fire zone, Winston throws the post.

That wouldn't be a terrible decision except that his running back is uncovered in

the flat.

Winston's greatest weakness right now is that he's too aggressive and tries to do too much, and his greatest strength is everything else. He is a very exciting prospect who could start on some NFL rosters right now. Once he learns to take what the defense gives him instead of trying to turn everything into a big play, he'll be a monster.

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.png)

.png)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)