Quarterback Jacob Coker's transfer from Florida State to

Alabama was one of the big stories of this college football offseason. FSU QB

coach Randy Sanders said Coker was "probably the best I've seen in 25 years at

throwing it" — even better than Heisman winner Jameis Winston. "I've never had

anybody with his size who throws it as well as he does." After seeing those

comments, I had to take a look.

I don't want to rehash what's already been written. Coker's got

prototypical size (6'5" and 230 pounds). He's got good arm strength and nice

touch. Finally, he's a pretty good athlete. He's got decent straight-line

speed, is fairly elusive in small spaces and can throw on the move.

At times Coker looks a little like Winston, but he isn't yet a complete quarterback. There's plenty of room for improvement in his accuracy and decision-making.

Coker's accuracy is difficult to evaluate because of the

small sample size but also because many of his passes were in the three-step

game. However, in the spring game he was repeatedly off the mark on his short

throws.

There were a couple of slants thrown too high or behind receivers. There was also a drag route thrown high and inside that resulted in an interception.

A good read on this play in the spring game is negated by an overthrow. Coker's footwork is stiff in the pocket and he doesn't fully step into the throw.

I can't totally blame Coker for this throw on the hitch-n-go

because the route is horrible — the receiver overemphasizes the hitch and disrupts the timing. Still, this is not a difficult throw. Again Coker doesn't step into the throw.

Coker threw a couple of deeper balls down the sideline in

the spring game. This deep curl stood out because, although it was complete, it

was put too far inside. The cornerback slipped on the cut and wasn't able to

make a play on the ball, but that's not where you want that throw to go because...

A couple of plays later Coker tried to throw a backshoulder

fade and the ball was again too far inside and should have been picked off.

The spring game isn't an ideal setting for analyzing a player, but because Coker saw all of his regular-season action in garbage time, the vast majority of those throws were in the quick game — and thus not very informative.

That said, Coker's accuracy in the regular season was better but still lacking. There was a bubble screen thrown at a receiver's ankles and a drag thrown behind his target. This is a simple quick-in route in Levels (a high-low concept), but Coker doesn't step into the throw, causing it to sail high, through the receiver's grip and into the hands of an NC State safety.

The spring game isn't an ideal setting for analyzing a player, but because Coker saw all of his regular-season action in garbage time, the vast majority of those throws were in the quick game — and thus not very informative.

That said, Coker's accuracy in the regular season was better but still lacking. There was a bubble screen thrown at a receiver's ankles and a drag thrown behind his target. This is a simple quick-in route in Levels (a high-low concept), but Coker doesn't step into the throw, causing it to sail high, through the receiver's grip and into the hands of an NC State safety.

Still, Coker flashed good accuracy. For instance, there's the Winstonesque play in the first gif. There was also a really well-thrown ball on a deep wheel route against NC State while Coker was rolling to his right. That pass fell incomplete but it was off by only inches. From what I can tell, Coker's inconsistent accuracy stems from his footwork breaking down when the pocket is closing in; it should be fixable.

I like a lot of what I see from Coker as a decision-maker. He consistently recognized man or loose coverage and was able to exploit favorable matchups on the outside (there are tons of examples of Coker throwing hitches and quick-outs). The only problem is that he needs to make those decisions quicker.

Coker makes the correct read on this play but he makes it too slowly. The offense is running a horizontal stretch on the linebacker, forcing him to pick either the slot's drag route or the fullback's flat route. By the time Coker decides which receiver to target (and because of a coverage breakdown he could have thrown to either), the blitzer off the edge is in his face and likely would have disrupted or prevented the throw in live action.

Here's another example of hesitation, this time in an actual game (NC State). Coker steps into the pocket like a veteran on this play but he held onto the ball too long and seemed to have

locked on to one receiver. He has an obvious checkdown on the drag route; the ball

should have been dumped off before that receiver had to spin around.

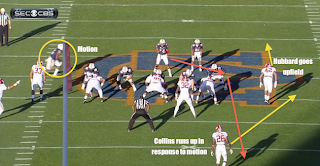

This was an encouraging play until the end. There's nothing particularly notable about the pre-snap

alignment from the defense except that one of the linebackers is showing blitz.

However, the field safety makes a subtle move late, coming up from his deep

position and sliding over the top of the slot. This alerted Coker

that the nickelback likely would not be covering the slot and thus was probably

coming on a blitz.

Based on his footwork and the fact that he rushed the throw, I think Coker did recognize pressure. But I think he chose the wrong route. He wanted to target the tight end, who was in a favorable matchup vs. a defensive end, but he was running a slow-developing corner route and had a safety over the top covering the deep half of the field. Meanwhile, the slot receiver on the other side of the field was running a quick-out with a large cushion. Under pressure, Coker lofted the ball in the tight end's general direction before the receiver had even made his cut, and the ball fell incomplete.

So that play was almost a success. Let's look at some more encouraging plays.

On the stat sheet, this play — an incompletion — is a failure. In reality, it's an example of ball security (game manager, anyone?). From the pre-snap read it appears that Maryland is in Cover 3 (three deep and four underneath zone defenders). Coker wants to exploit the boundary-side flat with the out route. But notice how quickly the boundary-side outside linebacker gets into his drop and gets his head around. Coker cocks his arm back but sees the defender in the way and holds onto the ball. If he had tried to throw the out route, it probably would have resulted in a pick-six. Knowing he’s got no other immediate outlet since both backs initially stayed in for protection, he smartly throws it away. (I can't tell what the two receivers on the bottom were running but they look like slower developing routes.)

This is a more obvious success. The defense is playing Cover 4 to the field side, meaning the safety is taking the slot receiver since he threatens the defense vertically. That leaves the cornerback on an island against the outside receiver, 6'5" Kelvin Benjamin. A smart QB will see that and take his shot — and that's exactly what Coker does. Give your big man a chance to be a playmaker.

Coker has physical talent in spades but still needs to clean up his game if he's going to win the starting job in Tuscaloosa. It starts with keeping his footwork tidy when the pressure is getting to him. Add quicker decision-making and Coker will be a formidable weapon at quarterback.

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.png)

.png)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)